Hauptseminar: 'Middle English Dream Visions'

Dozent: Dr. R. Holtei

Sommersemester 1996

| Contents |

page

|

|

| I. Introduction |

3

|

|

|

i. methods and devices of interpretation

|

||

| II. The spiritual and the material |

4

|

|

|

i. Pearl: jewel -> maiden -> soul

|

||

|

ii. Paradise: 'erber' -> earthly paradise -> Heaven

|

||

|

iii.

Love: dreamer -> Heavenly Lover (Jesus)

|

||

|

iv. Jerusalem: old and new

|

||

| III. Conclusion |

16

|

|

| IV. Bibliography |

18

|

|

Ever since 'Pearl' was first published in 1864 for the modern world the poem has been a constant subject of considerable research and disputes about its origins and interpretations. What can one say about a poem which was written six centuries ago, in a time that was so different from ours? Many scholars have argued whether the 'Pearl' was an elegy on the death of a loved child, an allegory on theological debates or a consolatio.

Of course, a lot of scholars have also debated about the spiritual and the material duality in and of the 'Pearl', and this is the subject of the following term paper. Philosophers both classical like Boethius and medieval like Thomas Aquinas had different opinions about spirituality and materiality.

While using four examples from the 'Pearl' poem, namely the

i. meaning of pearl: jewel -> maiden -> soul

ii. meaning of paradise: 'erber' -> earthly paradise ->Heaven

iii. meaning of love: dreamer and Jesus

iv. meaning of Jerusalem: old and new

I want to show the duality of the spiritual and the material (physical). In these four examples, I want to prove that the author deliberately used a threefold division to create the resulting sum of 'twelve' as the important and recurring numerical symbol of the pearl.

But before analyzing the presented subject, here are some directions

to the methods I used: first, we will look into the three above mentioned

examples taken from the 'Pearl' text from the spiritual and the material

point of view.

Moreover, I deliberately used the alchemistic word 'materiality' instead

of materialism for the word materialism has too many economical and

political connotations to it. The next step is to investigate whether

the author deliberately used ambigious images to show that the old alchemistic

lore 'As above, so below' was still valid during the late fourteenth

century and that the author kept closely to the mysterical number 'twelve'

and arranged the 'Pearl' text around this particular number.

This particular method forces me to ignore the immediate interpretation of 'The Pearl' text itself and especially the scheme of word-links.

A last remark is made here on the quotations in this paper, all Middle

English quotations are from the standard edition by E.V. Gordon, the

English translations underneath the original texts have been translated

by myself. Some primary and secondary literature will occur quite often,

especially the 'Pearl' I have shortened to the Italic signet TP. Single

words quoted from the text are also written in Italics , followed by

chapters and lines. Latin numerals following the titles or signets mark

either books, chapters or stanzas, Arabic numerals mark either lines

or pages.

Unfortunately, I realized too late that the chosen form of presentation

of the four examples is in an arbitrary order. The arrangement would

have beenbetter beginning with the 'erber' than followed by pearl and

Heaven (as this is the division used in the poem) but because of lack

of time, I used this particular order.

II. The spiritual and the material

Spirituality has always been connected with gods and deities. In the

early times of mankind it had the shroud of forbiddeness around it.

Only those who were learned in the ancient magics or rituals were allowed

to participate or discuss spirituality.

Later, when Greek and Roman philosophers sought a new way of explaining

the world with its mechanisms as how the worldly and heavenly orders

worked, spirituality was a way to explain the unexplained regions of

mankind, i.e. the corpereal substance (body, ratio) versus the ethereal

substance (soul, emotions) of all beings and things. Christian theologicans

tried to combine these concepts with the Christian belief. They did

not only distinguish between two contrasting schemes, i.e. spirituality

and materiality, but they had two threefold divisions: the corporeal,

the spiritual and the divine and the literal, the symbolic and the mystical.

Materiality was more easily defined. Everything that existed and could

be seen and touched was material. Man was very much part of this, inevitably

linked to the material.(Of course, some philosophers denied this as

well but this is not the subject of this paper).

i. Pearl: jewel -> maiden -> soul

The image of the pearl whether seen as a symbol for spirituality and the soul or as the material image of a jewel and wealth is in itself ambigious. The pearl symbol is not static but dynamic: its meaning develops not only in our everyday life but also in the poem as the text unfolds itself when reading it. The first impression the reader/audience gets of the 'Pearl' is that of a priceless pearl without fault:

| "I dewyne, fordolked of luf-daungere, | ||

| Of žat pryuy perle withouten spot." | ||

|

(TP,

I, ll. 11-12)

|

||

| (I pine away, wounded by the power of love, | ||

| for my pearl without a spot.) |

This last line of

the first stanza is repeated at the end of each line of the opening stanza-group

of the first book/chapter of the 'Pearl' poem to emphasize the wordly

part of the meaning. In the poem the dreamer the first-person narrator)

explains that this pearl was not only a piece of jewelry but he uses this

imagery as a metaphor forhis dead child or loved one.

Here, the pearl begins its transcending journey from a natural objet

d'art to a more philosophical meaning:

While the story unfolds

itself, the reader soon finds out that there is more to discover about

the pearl image than one might think at first. The dreamer insists that

the pearl he had lost is his child who had the fair and shining complexion

of a pearl and denies that there is something ethereal which he cannot

properly grasp with his ratio.

But let me return to the spirituality of the pearl symbol: the image

of the pearl which transcends from the mere shell of materiality, becomes

something more ethereal and hard to understand in the second part of

the poem ( from ll. 271 ff.). During the dream of the jeweller in which

he converses with the pearlmaiden, it becomes clear that the pearl symbol

turns into a philosophical and theological concept, i.e. the soul. While

the dreamer mourns not entirely for his loved one but more for the material

jewel he has lost, for he calls himself a jeweller now (TP, V, l. 25).

This emphasizes his feeling that the child/maiden is his own, as the

pearl is the property of a jeweller. Though the dreamer/jeweller now

claims that he is the rightful owner to the pearl, in the spiritual

way he is not. He owned the mortal body but not the immortal pearl,

i.e. the soul. The maiden reprimands him and tries to make him understand

the difference:

The maiden tries to

show that although it is important to believe in the material side of

all things, it is important as to appreciate the spiritual and eventually

the divine side of things. True joy cannot be experienced from material/worldly

things and if someone does so, his/her reason (or ratio) is used in a

mad or unreasonable manner, for although man can use his reason, he has

to abide God's law.

Furthermore, she explains that the material aspect of a thing or being

is only important if combined with God's grace and forgiveness: Here, the two concepts of the spiritual and the material symbol of

the pearl are seemingly at war with each other. The maiden represents

the spiritual side of all things and beings, i.e. the Lord, Trinity

and soul, whereas the jeweller who cannot understand that the pearl

they are talking about is represented in both worlds, refuses to the

spiritual side of it and appreciates only the very 'down to earth' image

of the pearl, i.e. wealth, he very much belongs to the material world.

But the jeweller is somewhat obstinate and does not want to understand

(perhaps the dreamer was a little too exaggerated by the author, i.e.

dreamer in dream visions are always naive and not too 'bright'), as

if the author wanted to confront his contemporaries with their own mirror-images,

of wanting 'more' (TP, III, ll.135.136) of worldly fortune. The transcending journey of the spiritual and the material

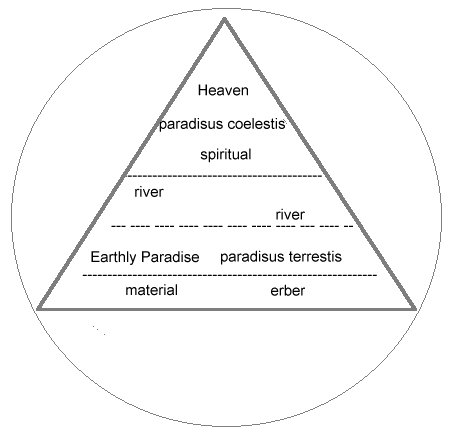

ii. Paradise: 'erber' -> earthly paradise -> Heaven

The paradise concept can be divided into three stages: the earthly

'erber' as an imperfect locus amoenus, the earthly paradise which is

the paradisus terrestris of the dream and the Heavenly Paradise, the

paradisus coelestis of the new order.

and ready to be

harvested "Quene corne is coruen wyth croke kene" (TP, I, l.40) the

author makes clear that this is not a perfect setting but an earthly

image of the locus amoenus where decay fulfills the cycle of life on

earth. The garden which is synonymous with the world, is a place of

sorrow, hardship and yet of considerable beauty which foreshadows the

Heavenly 'erber' in the dream proper. In the garden, the pearl was lost,

and yet she can be found in a different form in the next step, beauty

returning to beauty. The garden in the dream looks familiar at first

but soon the dreamer findsout that there are differences; that the surrounding

landscape has an unearthly touch: However, he is granted a glimpse of the 'paradisus coelestis' in his

vision. The superior beauty of this divine world is highly emphasized

by the author:

The concept of the author's division is closely connected to the ancient

lores of alchemy and magic. One is reminded of illustrations of a triangle

surrounding the eye of God. I have used this very image (minus the eye)

to illustrate the hierarchal structure of the different spheres of the

'erber' scenes in the dream proper.

The three stages/spheres of the garden iii. Love: dreamer - Heavenly Prince (Jesus)

Just as the material and the spiritual are reflected in the pearl

symbol and the threefold paradise concept, there is a certain ambiguity

in the way that the dreamer and the Heavenly Prince mourn respectively

courts the pearl-maiden. Both, dreamer and Heavenly Prince, use the

conventional language of courtly love. The dreamer, e.g. uses the concept

of courtly love as he grieves for his pearl:

It enhances the duality of the spiritual and the material in the symbol

of love, for it explains the three spheres of man's understanding of

love, that of the physical love between man and woman, the spiritual

love of man to the Lord and the divine love of God and the Lamb towards

the soul.

iv. Jerusalem: old and new

The vision of Jerusalem which the dreamer experiences in thelast part

of his visio, which is in fact a vision of a vision encountered by St.

John, represents the Heavenly Kingdom. The perfect state which cannot

be found on Earth. And although it is described as an outlandish sight,

it is the symbol for the Jerusalem of the material and the spiritual

world as well.

The actual Jerusalem of the late fourteenth century was very much

a city like any other in the Western and Far Eastern world. After the

decline of the kingdoms of the crusaders in the twelfth and thirteenth

century, Egyptian-Turkish nobles took over the supremacy of the city.

The Christian influence was only to be found in the Christian quarter

of Jerusalem where Franscican monks tended the grave of Christ. The

Western World had little to no influence and interest in this city and

it seemed as if it existed only in the imagination of people as the

Jerusalem of ancient times where David, Herodes and Jesus Christ lived

and created mysteries for the Westen and Far Eastern World. Jerusalem

was the actual place where Jesus Christ gave his own life to wash away

the sins of man:

"Syžen

in žat spote hit fro me sprange,

Ofte

haf I wayted wyschande žat wele

žat

wont wat whyle deuoyde my wrange

And

heuen my happe and al my hele -

(...)

To

ženke hir color so clad in clot!

O

moul, žou marrez a myry juele,

My

priury perle withouten spotte."

(Here

in this spot she came from me,

often

I have waited and pined to glean that pearl

brought

happiness and health.

(...)

In

dreams of her though wrapped in rot,

Oh Earth, you rob a rich and rare

and

precious pearl without a spot.)

"Bot,

jueler gente, if žou schal lose

žy joy for a gemme žat že watz lef,

Me

žynk že put in a mad porpose,

And

busyez že aboute a raysoun bref;"

(But

gentle jeweller since you lose

your

joy because you lost a gem,

I

think you follow a mad purpose

and

busy yourself with a momentary whim.)

"For

žat žou lestez watz bot a rose

žat flowred and foyled as leynde hyt gef;

now

žur kynde of že kyste žat hyt con close

To

a perle of prys hit is put in pref."

(For

what you lost was but a rose

that

flowered and finally withered in time.

Now

healed within this heavenly abode,

and

became a blessed pearl of beauty.)

But the subtleties

of this concept are lost on the dreamer for although he accepts what the

maiden has said (TP, V, ll. 277ff.) he thinks that he can reclaim his

'perle' (TP, V,l. 258) in a worldly manner.

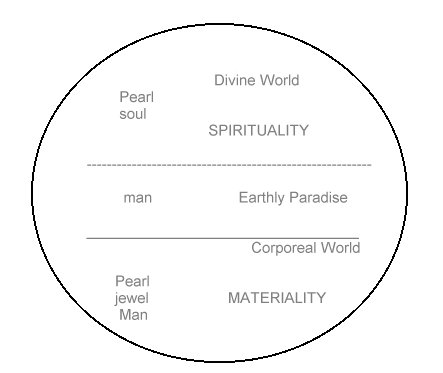

The material world and the spiritual (combined with the divine) represented

by the world (jewel) and the pearl (maiden and soul) are connected with

each other to the point where the spiritual pearl leaves the corporeal

pearl behind to enter Heaven. The maiden incorporates both the spirituality

of man and also the Divine, for the soul was created by God and is in

itself part of the Lord and his power. The pearl transcends through

three stages (that of jewel, child, maiden) until it reaches the divine.

Illustration No. 1

The 'erber' described in the beginning of the poem is a very earthly

garden: with 'gresse' (TP, I, l.10) and a lot of colourful herbs and

flowers (TP, I,ll.25-27). It seems as if it is a garden that one can

still find in the countryside and moreover, could have been found during

medieval times. The beauty of the garden or 'erber' is savagely connected

with decay and death (the eventual destiny of mankind) for although

the garden is in full bloom:

"Gilofre,

gyngure, and gromylyoun,

and

pyonys powdered ay bytwene."

(Gillyflower,

ginger and gromwell bred

and

peonies in between.)

"Holtewodez

bry t aboute hem bydez

Of

bolle as blwe as ble of Ynde;

As

bornyst syluer že lef on slydez,"

(Below

each, far forests were

of

boles blue as the ink of India

as

lovely silver the leaves were laced.)

The dreamer cannot

detect any hints of decay, only beauty. The only evil which is apparent

comes from the dreamer himself as he wanders through the garden (TP, III,

ll.151-154). After some hesitant remarks about being in 'paradyse' (TP,III,

l.137), the dreamer ackowledges 'Eden'. But he onlyexperiences the 'paradisus

terrestris', the earthly paradise, still a world apart from the 'real'

paradise on the other side of the river. But this transition marks the

final step towards the Heavenly Paradise(paradisus coelestis) and the

change of the dreamer's state of mind. Although the dreamer is now onan

elevated sphere between the material (Earth) and the spiritual (Heaven)

he remains connected tothe material. In order to enter the Heavenly Paradise

he has to cross the river which he cannot forhe is still material body.

"I

stod as stylle as dased quayle

For

ferly of žat frelich fygure,

žat felde I naw er reste ne trauayle,

So

watz I ravyste with glymme pure.

For

I dar say with conciens sure,

Hade

bodyly burne abiden žat bone,

ža

alle clerkez hym hade in cure,

His

lyf mer loste anvnder moone."

(I

stood as still as a dazed quail

for

that fair and noble figure,

that

I felt neither rest nor hardship

I

was so ravished by that pure radiance

for

I say with pure conscience/mind

had

a mortal body born that boon

that

all clerks could find no cure

for

his life were lost beneath the moon.)

The dreamer is awestruck

by the beauty of this place which he is hardly able to describe. Here,

true spirituality resides to which man has no entry. The ethereal realm

remains closed to him and he is granted only a vision. The Heavenly Paradise

and the Heavenly City are the concepts of the spiritual meaning of the

garden because there are the same components (trees, flowers, etc) but

composed in another differrent manner.

Illustration No. 2

Illustration No. 2

"I

dewyne, fordolked of luf-daungere

Of

žat pryuy perle withouten spot."

(I

pine wounded ba the power of love,

for

my pearl without a spot.)

Here, he pines like

a young man for a lost loved one. The author uses the courtly love language

to create compassion so that the reader/audience can relate to the state

of loss the dreamer is in.

Moreover, the dreamer treats the maiden reverently as he encounters her

for the first time:

"To

calle hyr lyste con me enchace

Bot

baysment gef myn hert a brunt;"

(To

call her nearer I desired

but

my amazement made my heart miss a beat.)

He desires to call

out to her but bewilderment disturbs his heartbeat. Like a lover would

with his loved one he describes the maiden until full recognition sets

in of what she really is. The courtly love conceptalthough used in medieval

times to seduce spiritually , here is the representative of the material

world.

It is not surprising that the dreamer would use a concept that is unmistakably

bound to his material world but Jesus as the Heavenly Prince woos and

marries the maiden with the words of a lover in medieval romance:

"Cum

hyder to me, my lemman sweete,

For

mote ne spot is non in the."

(Come

hither to me, my sweet love

for

there is not a fault in you.)

Of course, the meaning

of these words are totally spiritual, i.e. the most important moment for

Christians when their souls are redeemed. Only the words, not their meaning

belong to the material world whereas the act of redemption belongs purely

to the realm of spirituality. Here, St. Bonaventure's threefold division

of the literal (dreamer mourning his love and child), the symbolic (Jesus

wooing the pearl-maiden) and the mystical (redemption of man's soul can

be used.

"

žat is žet cyté žat the Lombe condfonde

To

soffer inne sor for manez sake,

že olde Jerusalem to vnderstonde,

for

žere že olde gulte watz don slake."

(That

is the city in which the Lamb could be found

to

suffer for man's sake,

and

it is known as Old Jerusalem,

there

he took away all sin and guilt.)

The

Jerusalem of the late fourteenth century had little to do with the Jerusalem

of the Old and New Testament where it was depicted as the ancient city

of David and the martyrdom of Jesus Christ.

People had a somewhat pre-conceived image of Jerusalem which was in

a material fashion. They either saw it as the Jerusalem of old which

did not exist any longer or as the Jerusalem of their own time which

declined more and more.

The dreamer, however, is granted a different sight of Jerusalem, that

is the Heavenly City as it is described in the Apocalypse of the apostle

John:

| "By onde že brok, fro me warde keued, | ||

| žat schyrrer žen sunne with schaftez schon. | ||

| In že Apocalypse is že fasoun preued, | ||

| As deuysez hit žet apostel John." | ||

|

(TP,

XVII, ll. 981-984)

|

||

| (Beyond the brooke, near a hill's head, | ||

| that city then shone in the sun. | ||

| In the Apocalypse is the fashion shown | ||

| as apostle John described it.) | ||

Here, the divine Jerusalem emerges from the more material and spiritual Jerusalem of the earthly abode. The author portrays the city of Jerusalem as threefold, meaning the Jerusalem of the late fourteenth century as the material city, the Jerusalem of old as the city belonging to the spiritual and the Heavenly City as the divine.

II. Conclusion

One can say that the 'Pearl' poem portrays beautifully the duality

of both spiritual and material.

The author was well aware of the difficulties this might create but

nevertheless he shows that the material things are always reflected

in the spiritual. The old proverb 'As above, so below' which I mentioned

earlier in the introduction was, and from my point of view still is,

valid for this poem as well as for the world we live in though the theological

aspects of spirituality and materiality have shifted considerably over

the last decades.

All four examples from the text show the progression of man and the soul from the secular and material to the spiritual and eventually the divine sphere. Both, secular and divine connotations are made for the pearl, the 'erber', the love concept and Jerusalem. They work parallel to and with each other to roughly equate man's three sources of awareness: material (Earth, body), spiritual (intellect, inspiration)

and divine (Heaven, the Lord). Spirituality and materiality are dynamic

forces which are inseparably associated with each other. They reflect

each other, if one is missing the world is incomplete like a body lacking

the mind and vice versa.

Man can use both aspects, i.e. materiality and spirituality combined

with the divine, actively and also interchangably and the author of

the poem has done so artistically. By chosing the pearl symbol which

is in itself dual, i.e. symbol for the soul, God's grace, purity, innocence

and the Heavenly orders on the spiritual side and the symbol of wealth

and beauty on the material side, gives the whole existing world above

and below an ambigious meaning.

The pearl in the poem is a metaphor for the soul which cannot be seen

when residing in a living body below and yet if this body dies it is

set free to join the Lord above. Like the real pearl which is hidden

deep inside the oyster's flesh, far away from the eyes and the mind

of the beholder, it reveals itself when the oyster dies (i.e. is eaten).

The same with the garden symbol. It has the threefold division just

like the pearl symbol. The 'erber' of the first part of the poem represents

the world, the earthly paradise portrays the spiritual side of man and

the world where he is enabled to gain higher awareness of mind and the

paradisus coelestis shows the eventual destiny of man's life, i.e. the

redemption of the soul.

The threefold division of the material and the spiritual/divine can be found throughout the 'Pearl' poem and it portrays the deeply rooted obsession of the author with the Trinity and by square four (the four examples from this term paper), with the number 'twelve', which occurs everywhere in the poem. In alchemistic lore the number 'twelve' represents the four elements and cardinal points, i.e. Earth-North, Air-East, Fire-South and Water-West, and the basic principles (salt, sulphur and mercury).

Moreover, in Christian lore the number 'twelve' plays also an important role exhibiting the symbol of wholeness and perfection, i.e. the soul. It is depicting the perfection of God's creation, represented in the number 'twelve' and the symbol of the pearl.

Concluding, one can say that the 'Pearl' poem reflects the transition

of man and soul to a higher elevated, divine state of being. The very

structure of the poem reflects this transition of the worldly view of

a lost transitory good in the terms of the material; while during the

dream proper it elevates to the spiritual (dialogue with the pearl-maiden)

and, last but not least, presents itself (in its closing scene) as the

divine, that of the soul.

The pearl never changes its shape or origin; man decides whether it

is a small stone enamelled with mother-of-pearl turned into something

beautiful which belongs to the material world or the symbol of something

ethereal and divine belonging to the spiritual world.

IV. Bibliography

| Primary Literature | ||

| 1. Anderson, J.J., ed.: | 'Sir Gawain And the Green Knight', compl. | |

| with Pearl, Cleanness & Purity | ||

| Everyman Edition, 1991 (re-issue) | ||

| 2. Gordon, E.V., ed.: | 'Pearl', Oxford University Press, 1953 | |

| Secondary Literature | ||

| 1. Aquinas, Thomas: | 'Summa Theologica', Vol. One, | |

| William Benton Publisher, Encyclopaedia | ||

| Britannica Inc., London 1972 | ||

| 2. Blenkner, Louis: | 'The Theological Structure Of Pearl', from | |

| Traditio, XXIV, Fordham University Press 1968 | ||

| 3. Bonaventure, St.: | 'The Mind's Road To God', Opera Omnia | |

| translated by George Boas, New York, 1953 | ||

| 4. Finch, Casey: | 'Incarnational Art', from The Complete | |

| Works Of The Pearl Author, 1990 | ||

| 5. Hillmann, Mary: | 'Some Debatable Words In Pearl...', from | |

| The Middle English Pearl, ed. by John | ||

| Conley, University of Notre Dame Press, | ||

| London, 1972 | ||

| 6. Stern, Milton: | 'An Approach To Pearl', from The Middle | |

| English Pearl, ed. by John Conley | ||

| University of Notre Dame Press, London,1972 |